Quick Navigation

You know that feeling when you're in a deep forest, surrounded by towering trees, and the air just feels… cleaner? Or when you see a lush green field and sense a kind of quiet, humming energy? That's not just your imagination. You're literally standing in the middle of the planet's most important, most widespread, and frankly, most underrated chemical reaction. I'm talking about photosynthesis, of course.

It's the process that literally built the world as we know it. Without it, we wouldn't have oxygen to breathe, food to eat, or fossil fuels to power our cars (for better or worse). We learn the basics in school—plants, sunlight, water, oxygen—but the real story is so much more intricate and fascinating. It's a microscopic solar-powered factory operating in every green leaf, and understanding it changes how you see the natural world.

I remember trying to grow tomatoes on a shady balcony years ago. Total failure. They grew tall and spindly, with maybe one pathetic fruit. I didn't get it then, but I was starving them of the one thing they needed most: the fuel for photosynthesis. Sunlight wasn't just a nice-to-have; it was the core ingredient. That personal failure got me curious.

Let's break this down, not like a textbook, but like we're peeking into the leaf's private kitchen.

The Two-Part Dance: Light Reactions and the Calvin Cycle

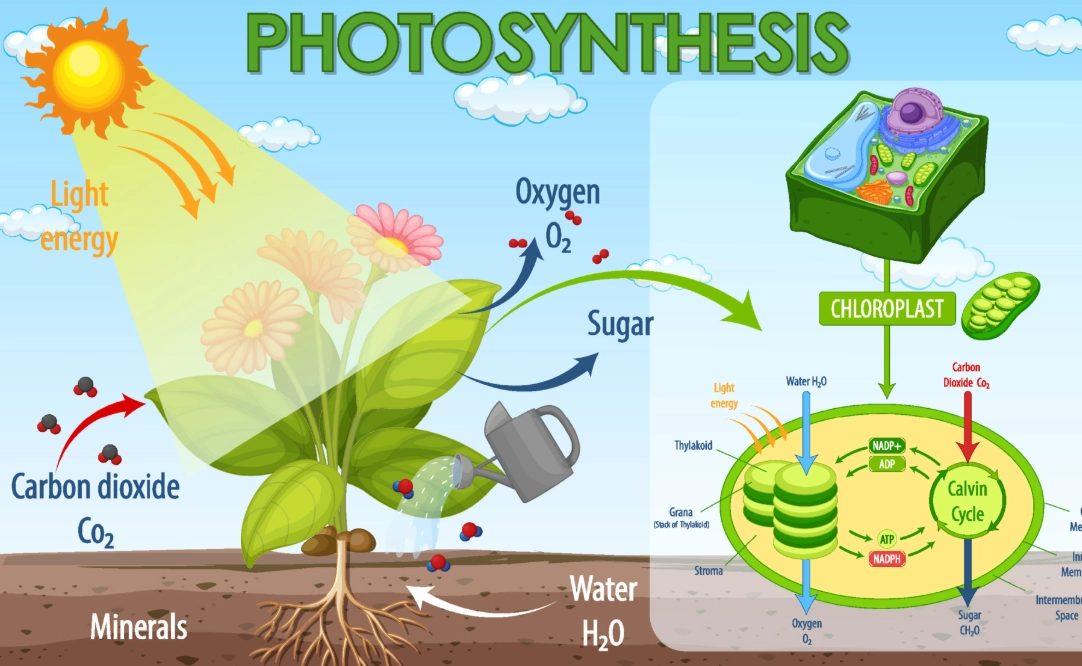

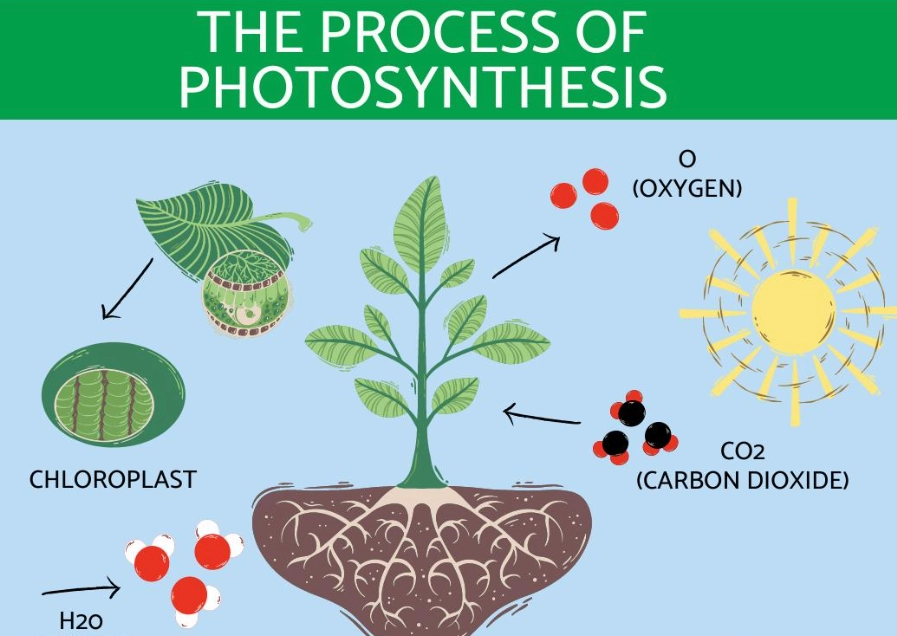

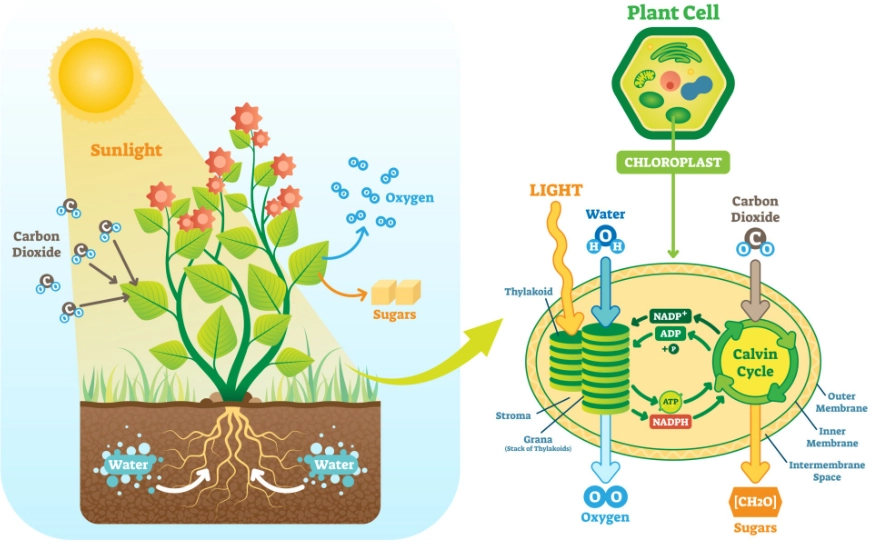

Most people think photosynthesis is one thing. It's actually a beautifully coordinated two-act play happening inside tiny organelles called chloroplasts. Get ready for the main event.

Act One: The Light-Dependent Reactions (Catching the Sun's Rays)

This is where the solar panels kick in. Chlorophyll, that famous green pigment, and other helper pigments are arranged in structures called photosystems. They act like antennae, absorbing photons of light. When light hits, it's like a tiny energy packet getting dumped into the system.

This energy has a job: to split water molecules. This is a huge deal. The plant takes H₂O and, using light energy, rips it apart. The oxygen atoms from the water pair up and are released as waste gas—the O₂ we breathe. Seriously, the oxygen in every breath you take is a byproduct of a plant splitting water. Let that sink in.

The energy from light also creates two crucial energy-carrier molecules: ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and NADPH. Think of these as fully charged, reusable batteries. They're packed with energy and are now ready to be shipped to the second act of the photosynthesis show. This whole first act absolutely requires light. No sun, no charged batteries.

Pretty neat, right? But we've only made energy carriers and oxygen. Where's the food?

Act Two: The Light-Independent Reactions (The Calvin Cycle, or Building the Food)

This is where the actual sugar gets built, and it can happen in the light or dark, as long as those "charged batteries" (ATP and NADPH) from Act One are available. The star of this show is an enzyme with a terrible name: RuBisCO. It might have a clunky acronym, but it's arguably the most abundant protein on Earth. Its job is critical.

RuBisCO grabs carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the air and attaches it to an existing 5-carbon molecule. The resulting unstable 6-carbon molecule immediately breaks apart into two 3-carbon molecules. Using the energy from our ATP and NADPH batteries, the plant then converts these 3-carbon molecules into a simple sugar called G3P.

Some of this G3P is used to regenerate the starting 5-carbon molecule, keeping the cycle going. The rest is used to build glucose, starch, cellulose—the very stuff of the plant. This cycle has to spin six times to make one molecule of glucose. It's a relentless, microscopic assembly line.

So, to summarize the entire photosynthesis equation you might remember: 6CO₂ + 6H₂O + Light Energy → C₆H₁₂O₆ (glucose) + 6O₂. The first part (H₂O + Light) makes O₂ and energy. The second part (CO₂ + Energy) makes the sugar.

Not All Photosynthesis is Created Equal: C3, C4, and CAM

Here's where it gets really interesting. Plants have evolved different "styles" of photosynthesis to deal with tricky environments like intense heat, drought, or strong sunlight. It's like different survival strategies.

| Type | How It Works (The Short Version) | Common Examples | Best For... | The Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3 Plants | The "original" method. Uses the Calvin Cycle directly in all leaf cells. Simple but prone to photorespiration in hot/dry conditions. | Rice, wheat, soybeans, most trees, about 85% of plant species. | Cool, moist environments. | Less efficient under heat and drought. |

| C4 Plants | Adds an extra step. First captures CO₂ into a 4-carbon molecule in outer leaf cells, then shuttles it to inner cells for the Calvin Cycle. This acts like a CO₂ pump, concentrating it for RuBisCO. | Corn, sugarcane, sorghum, many grasses. | Hot, sunny environments with moderate water. | Uses more energy upfront (more ATP) but saves water and avoids photorespiration. |

| CAM Plants | The ultimate water-savers. They open their stomata (leaf pores) at NIGHT to take in CO₂ and store it. Then, during the DAY when it's hot and dry, they close stomata and perform the Calvin Cycle using the stored CO₂. | Cacti, pineapples, aloe vera, orchids. | Extremely dry, desert environments. | Growth is often much slower because the process is limited by nighttime CO₂ storage. |

Looking at that table, you can see why C4 crops like corn are so productive in summer fields, and why your cactus doesn't just wither away on a sunny windowsill. They've hacked the basic photosynthesis system to survive their specific challenges. It's evolution's way of problem-solving.

What Factors Can Boost or Bust Photosynthesis?

It's not a constant, unchanging process. Think of it like an engine whose speed is controlled by several dials. Turn any one dial down too low, and it becomes the limiting factor—the bottleneck that slows everything down, no matter how high the other settings are. This is called the Law of Limiting Factors.

Here are the main dials:

- Light Intensity: More light generally means more energy, so photosynthesis speeds up… but only to a point. Once all the chlorophyll molecules are busy, extra light does nothing and can even cause damage (think sunburn on a leaf). Shade plants hit their max at much lower light levels than sun plants.

- Carbon Dioxide Concentration: This is often the limiting factor in nature. More CO₂ usually means more raw material for RuBisCO to work with. This is why CO₂ is sometimes pumped into commercial greenhouses to boost crop yields. The natural level in the air is about 0.04%, which is quite low.

- Temperature: Photosynthesis is driven by enzymes, and enzymes love a specific temperature range. Too cold (below 10°C/50°F), and they work sluggishly. Too hot (above 40°C/104°F for many plants), and they start to denature—their shape unravels and they stop working. The sweet spot is usually between 20-30°C (68-86°F).

- Water Availability: This is a big one. Water is a direct raw material (it's the H₂O that gets split). But more critically, when a plant is dry, it closes its stomata to save water. The moment it does that, it can't take in any more CO₂. Photosynthesis grinds to a halt not necessarily from lack of water as a chemical, but from lack of CO₂ due to closed doors.

- Mineral Availability: Certain minerals are crucial. Magnesium is at the heart of every chlorophyll molecule. Nitrogen is a key part of all proteins, including RuBisCO. A plant lacking these is like a factory missing steel or workers.

So, if you're a gardener wondering why your plant isn't thriving, run through this mental checklist. Is it getting enough light? Is it too hot on the patio? Have you been forgetting to water it (or maybe overwatering it, which rots the roots and also stops water uptake)? The answer usually lies in one of these factors.

Why Should You Care? Photosynthesis Beyond Biology Class

This isn't just academic. The process of photosynthesis touches everything.

The Oxygen You Breathe: Every breath is a gift from photosynthetic organisms, primarily oceanic phytoplankton. They produce an estimated 50-80% of Earth's oxygen. The Amazon rainforest is important, but the real "lungs of the planet" are in the ocean.

The Food You Eat: Directly or indirectly, all our food comes from photosynthesis. The wheat in your bread did it. The grass the cow ate did it. The algae that fed the fish did it. The energy that powers your body started as a sunbeam captured by a plant.

Fossil Fuels: Coal, oil, and natural gas are essentially ancient, concentrated sunlight. They're the remains of plants and algae from millions of years ago that stored the sun's energy via photosynthesis and then were buried and compressed. We're burning ancient photosynthesis.

Climate Change: Here's the critical link. Photosynthesis is the planet's primary natural carbon sink. Plants suck CO₂ out of the atmosphere and lock the carbon into their tissues (wood, leaves, roots) and the soil. Deforestation isn't just about losing trees; it's about actively removing the machinery that cleans our atmospheric carbon and replacing it with nothing, or worse, with activities that release more carbon. Research from institutions like NASA uses satellites to monitor global photosynthetic activity and its role in the carbon cycle, showing how vital forests and oceans are as buffers. Similarly, the U.S. Department of Agriculture conducts extensive research on how crop photosynthesis can be managed for both food security and carbon sequestration.

It's a double-edged sword. Rising CO₂ levels can, in the short term, act like fertilizer for some plants, potentially boosting photosynthesis (a concept called CO₂ fertilization). But the associated heat waves, droughts, and extreme weather from climate change often outweigh any benefit, stressing plants and shutting down the very process we rely on.

I find it humbling. Our entire technological civilization rests on this ancient, biological foundation. We can't replicate it efficiently at scale with solar panels yet. The best solar cells convert about 20-25% of sunlight to electricity. A leaf? Under ideal conditions, it maxes out at about 3-6% efficiency for storing energy as sugar. Seems low, right? But it also self-replicates, self-repairs, builds complex structures from air and water, and produces breathable oxygen as a byproduct. Our technology still has a long way to go.

Your Photosynthesis Questions, Answered

Look, at the end of the day, photosynthesis is more than a chapter in a biology book. It's the foundational metabolic process of our biosphere. It's the reason Earth is a vibrant, green, oxygen-rich world instead of a barren rock. Every time you see a plant, you're looking at a sophisticated, solar-powered life form running a chemical miracle that sustains almost everything else.

Next time you take a deep breath of fresh air, or bite into a piece of fruit, or even fill up your gas tank, you can think back to the quiet, relentless work happening in every green leaf and algal cell. It's a process that deserves our understanding, our respect, and our protection.