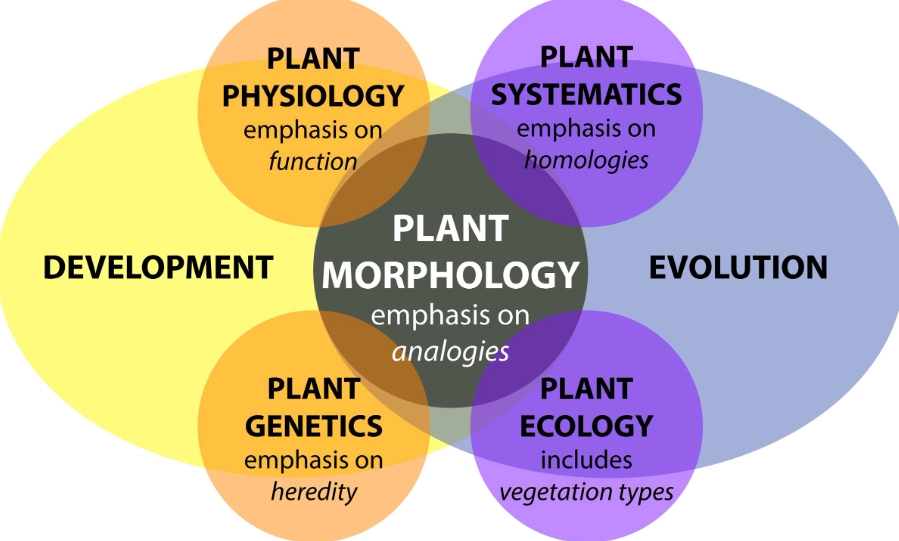

Let's be honest. When you hear "plant morphology," you might picture dusty textbooks and complex diagrams. I did too, when I first started. I killed a lot of plants by treating a succulent like a fern because I didn't know how to read their forms. That changed when I realized morphology is simply the study of a plant's physical form and structure. It's the plant's own built-in instruction manual. Once you learn the basic vocabulary – the shape of a leaf, the pattern of veins, how a stem grows – the green world stops being a blur and starts telling you stories.

This isn't about memorizing terms for a test. It's about gaining a practical skill. Whether you're trying to figure out if that seedling is a weed or a flower, why your houseplant is drooping, or just want to name that beautiful tree on your walk, plant morphology gives you the tools. It's the difference between guessing and knowing.

What You'll Learn

- Why Plant Morphology Matters for Gardeners (and Everyone Else)

- The Leaf Decoder: Your #1 Identification Tool

- Beyond the Green: Stems and Roots Tell Their Own Secrets

- Flowers & Fruits: The Advanced Morphology Class

- Putting It All Together: A Real-World Identification Walkthrough

- Your Plant Morphology Questions, Answered

Why Plant Morphology Matters for Gardeners (and Everyone Else)

You're not just looking at a plant; you're diagnosing it, identifying it, and understanding its needs. Morphology is the foundation.

I remember helping a friend who was convinced her new "shade-loving" plant was dying. The leaves were stretching out, pale, and the stems were weak and elongated. The plant was telling us it needed more light – a classic morphological sign called etiolation. The label was wrong, but the plant's form wasn't. That's the power of observation.

Here’s what a focus on morphology gets you:

- Accurate Identification: Distinguish edible berries from poisonous look-alikes by subtle differences in leaf arrangement or fruit structure.

- Health Diagnostics: Yellowing between leaf veins might indicate an iron deficiency. Mushy, black roots scream root rot. The symptoms are written in the plant's morphology.

- Informed Care: A plant with thick, fleshy leaves (like a jade plant) stores water and needs infrequent watering. A plant with large, thin leaves (like a hosta) loses water quickly and needs more consistent moisture.

- Appreciation: It transforms a walk in the park from a generic "look at the trees" to noticing the opposite branching of a maple versus the alternate branching of an oak.

The Leaf Decoder: Your #1 Identification Tool

Leaves are the plant's solar panels and its most consistent ID card. Flowers come and go, but leaves are there for most of the season. Let's break down the key features.

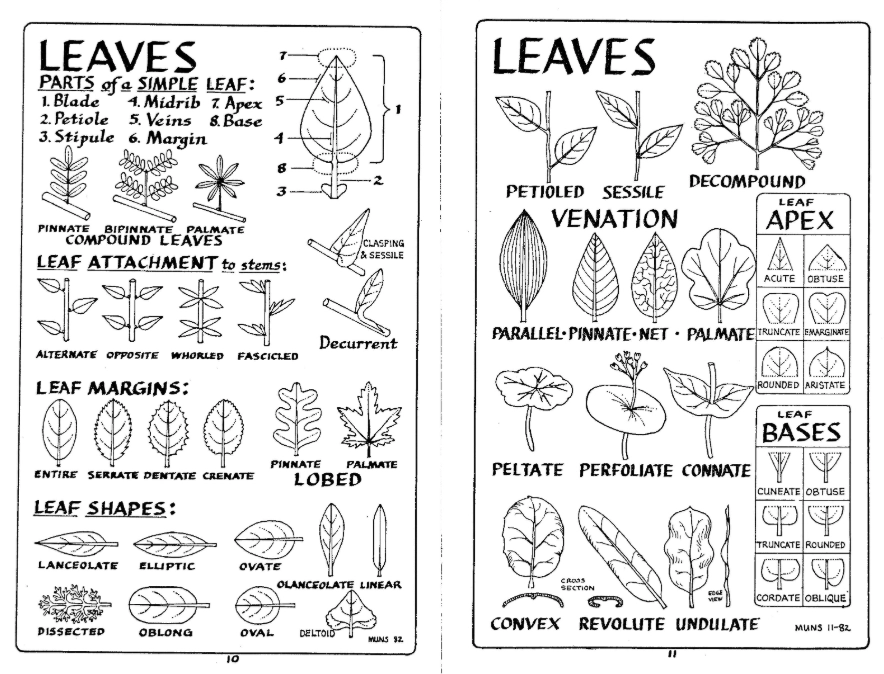

Leaf Arrangement: The Plant's Blueprint

How leaves are attached to the stem is your first major clue. Get this wrong, and your ID can veer off course.

- Alternate: One leaf per node, staggered along the stem. Think of oaks, roses, and sunflowers.

- Opposite: Two leaves per node, directly across from each other. Maples, mints, and dogwoods show this.

- Whorled: Three or more leaves per node, forming a circle around the stem. Less common, seen in some lilies and catalpa trees.

- Basal: All leaves coming from the base of the plant, like a dandelion or plantain.

A common pitfall? Mistaking a compound leaf for a branch with alternate leaves. Here's the trick: look for a bud. A bud is only found at the base of a leaf stem (petiole) or where a branch meets the main stem. If there's no bud at the base of each leaflet, you're looking at one compound leaf.

Leaf Shape, Margin, and Venation: The Fine Details

This is where you get specific. Instead of "jagged leaf," you learn to see "doubly serrate margin." It sounds complex, but it's just precise observation.

| Feature | Common Types | Example Plants | Quick Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape | Ovate, Lanceolate, Cordate, Linear | Lilac (cordate), Grasses (linear) | Trace the outline in your mind. Is it heart-shaped? Spear-tipped? |

| Margin | Entire, Serrate, Dentate, Lobed | Magnolia (entire), Beech (serrate), Oak (lobed) | Run your finger along the edge (carefully!). Smooth, teeth, or deep cuts? |

| Venation | Pinnate, Palmate, Parallel | Apple (pinnate), Maple (palmate), Lily (parallel) | Hold the leaf up to the light. Do veins branch from a midrib or spread from a point? |

I once spent an hour trying to ID a shrub as a type of cherry because of the leaf shape. The shape was right, but the venation was palmate, not pinnate. It was a viburnum. That one detail changed everything. Always cross-reference at least two morphological features.

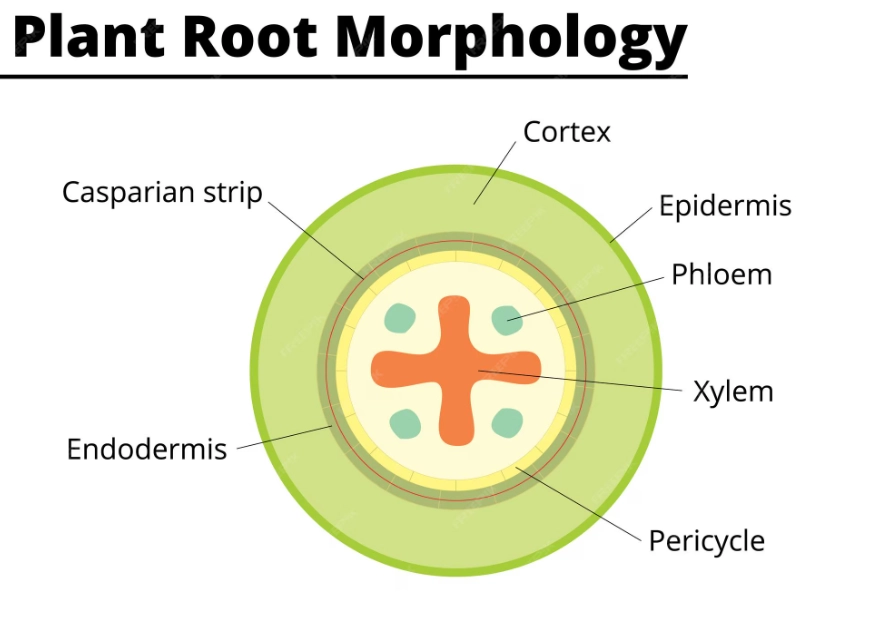

Beyond the Green: Stems and Roots Tell Their Own Secrets

We obsess over leaves and flowers, but the support system holds crucial data.

Stem Morphology: Is it herbaceous (soft, green) or woody (hard, bark-covered)? This tells you about its life cycle. Is it a vine with tendrils for climbing (peas) or aerial roots (ivy)? Look for unique features: thorns (modified branches, like on a rose), prickles (outgrowths of the epidermis, like on a raspberry), or spines (modified leaves, like on a cactus). Yes, they're all different, and that difference matters for ID and understanding how the plant defends itself.

Root Morphology: You can't always see it, but when you repot or troubleshoot, it's vital. A taproot system (one main root, like a carrot or dandelion) anchors deeply and accesses deep water. A fibrous root system (a network of similar-sized roots, like grasses) holds topsoil together brilliantly. If you're planting near a foundation, you'd want fibrous over taproot. Root morphology directly informs a plant's drought tolerance and soil preference.

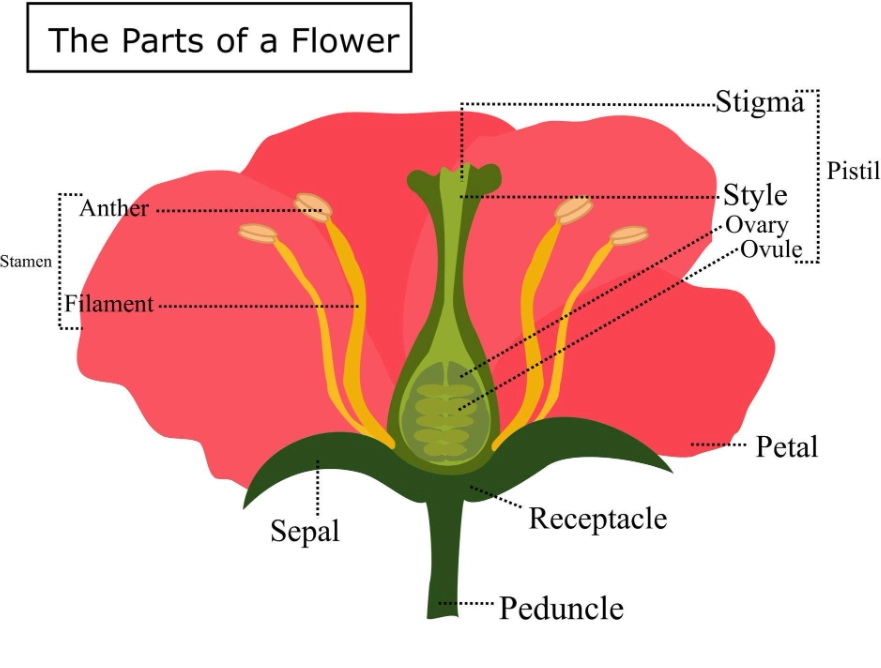

Flowers & Fruits: The Advanced Morphology Class

This is where botanists get really specific, but you don't need a PhD to use it.

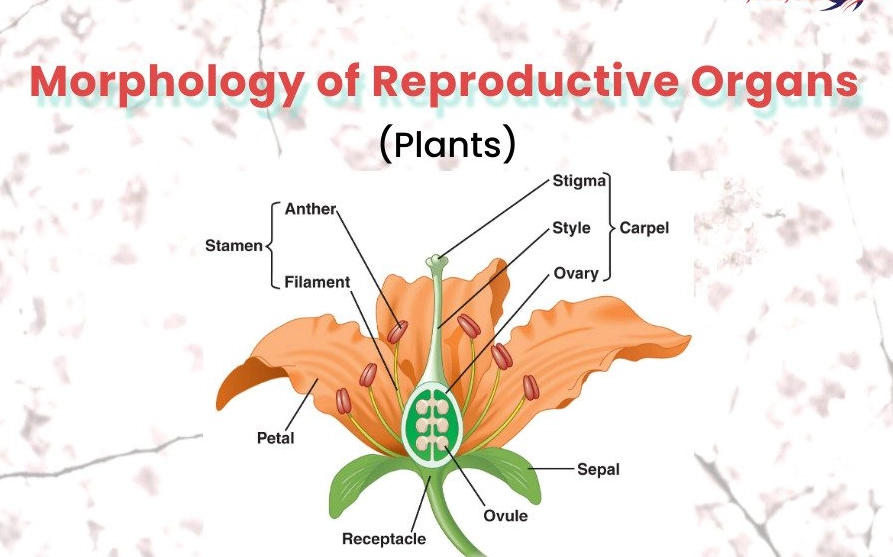

For flowers, start counting. Number of petals (are they fused or separate?), number of sepals, the arrangement of stamens. Is the flower symmetrical radially (like an apple blossom) or bilaterally (like an orchid or a pea flower)? The structure of the flower is intimately tied to its pollinator.

Fruit morphology is simply "what develops from the flower after pollination." Is it a fleshy berry (tomato), a drupe with a hard pit (peach), a dry pod (pea), or a nut (acorn)? This helps trace plant families. Plants in the rose family (Rosaceae) often produce a specific type of fruit called a pome – apples, pears, quince. See the connection?

Resources like the Encyclopædia Britannica's overview of plant morphology provide a solid academic foundation, while the detailed image databases from institutions like the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew are invaluable for seeing these traits in high resolution.

Putting It All Together: A Real-World Identification Walkthrough

Let's say you find a mystery plant in your yard.

Step 1: The Stem & Growth Habit. Is it a tree, shrub, or herb? The stem is woody and branching from the base – it's a shrub.

Step 2: Leaf Arrangement. You see two leaves growing directly opposite each other on the stem. Immediately, you rule out a huge number of plants (like oaks, roses). You're in the "opposite" category.

Step 3: Leaf Details. Leaves are simple (not compound), ovate in shape, with a serrated margin and pinnate venation.

Step 4: Flowers/Fruits. It has small, tubular, bilaterally symmetrical lavender flowers growing in clusters at the stem tips.

Putting it together: Woody shrub + opposite leaves + tubular bilabiate flowers = High probability it's in the mint family (Lamiaceae). A quick check reveals a square stem (a mint family hallmark) and a fragrant smell when crushed. You've likely identified a type of salvia or agastache. Without flowers, steps 1-3 would have still narrowed it down massively.

This systematic approach beats random Google searches every time.

Your Plant Morphology Questions, Answered

Start small. Pick one plant in your home or garden tomorrow. Don't just glance at it. Ask: How are the leaves arranged? What shape are they? Feel the stem. You're not just looking anymore; you're reading. And that changes everything.