You see a ladybug on a leaf. You watch a butterfly flit by. Maybe you swat a mosquito. We interact with adult insects all the time, but that's just the final act of a much longer, stranger story. The insect life cycle is the hidden drama happening in your garden soil, under tree bark, and in that forgotten bucket of rainwater. Understanding it isn't just trivia—it changes how you see the world, manage pests, and protect pollinators. It's the difference between seeing a bug and understanding a biography.

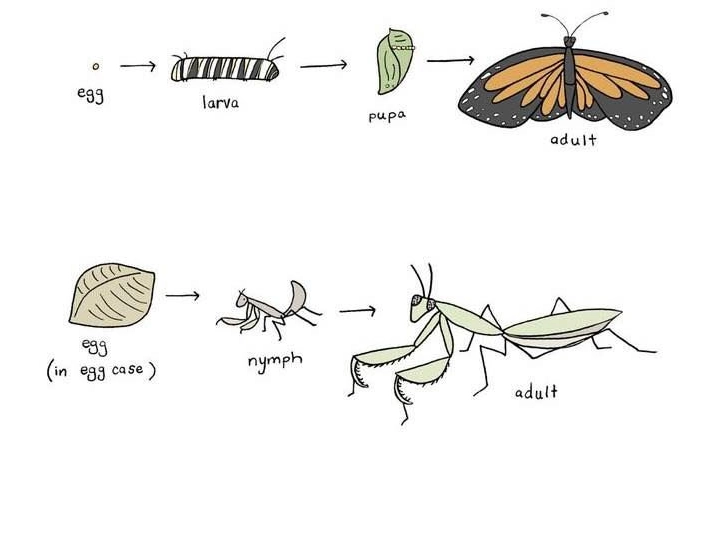

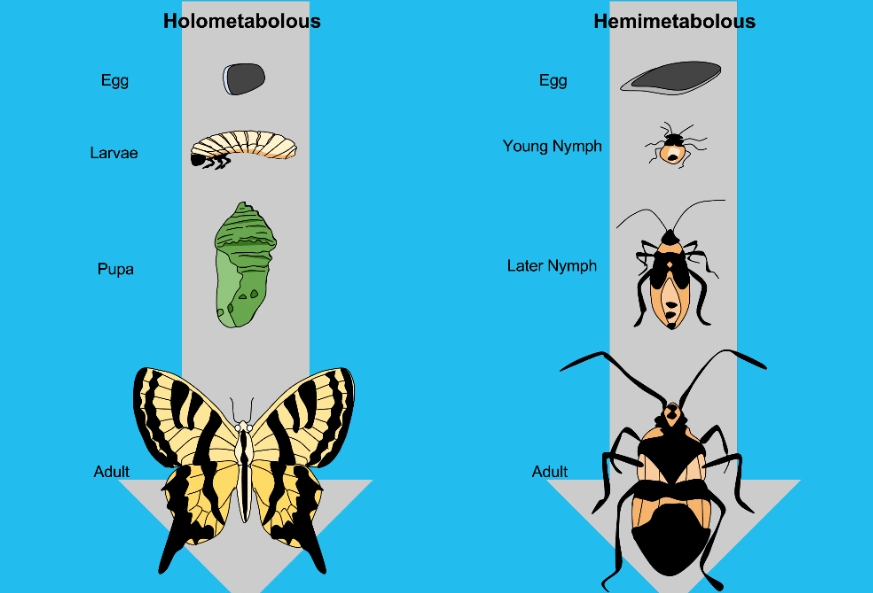

Most people get the butterfly part: egg, caterpillar, chrysalis, butterfly. That's called complete metamorphosis (or holometaboly). But nearly half of all insect species, including grasshoppers, dragonflies, and cockroaches, do something completely different called incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetaboly). They don't have a pupal stage. The young, called nymphs, look like tiny, wingless versions of the adults and just grow and molt until they're ready. Missing this fundamental split is the first big gap in most people's insect knowledge.

Your Quick Guide to Bug Life

The Two Roads of Insect Development

Think of it as two different biological strategies. One is a total reboot. The other is a continuous upgrade.

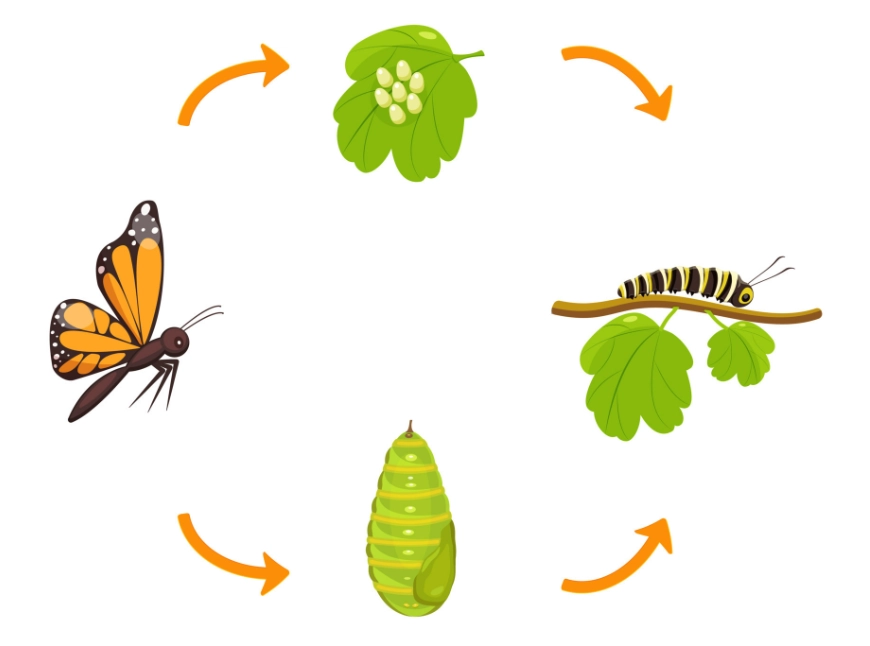

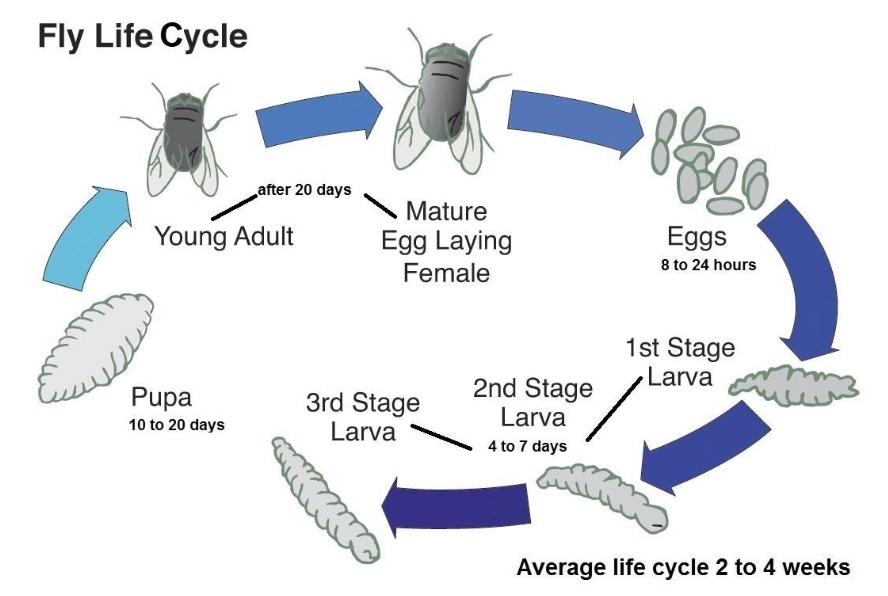

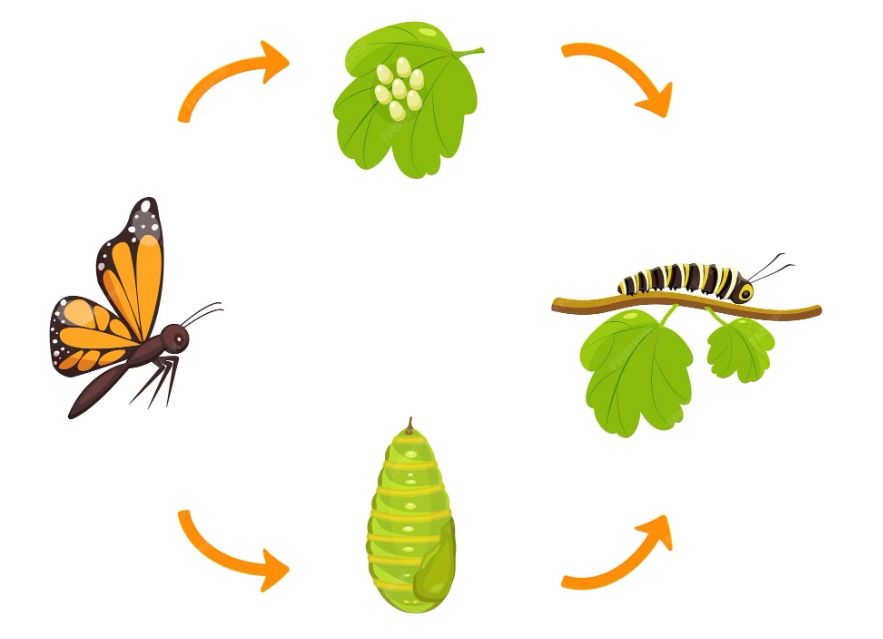

The Total Reboot: Complete Metamorphosis

This is the Hollywood blockbuster of life cycles. Beetles, butterflies, bees, flies, ants—they all follow this path. The key is the pupal stage. The larval stage (caterpillar, grub, maggot) is an eating machine designed for one job: consume and grow. It looks nothing like the parent. Then it seals itself up, and inside the pupa, its body is literally liquefied and rebuilt from scratch into the winged, reproductive adult. The larval and adult stages occupy completely different ecological niches, so they don't compete for food. A caterpillar eats leaves; a butterfly sips nectar. Pretty clever.

The Continuous Upgrade: Incomplete Metamorphosis

Dragonflies, grasshoppers, mantises, and true bugs take this route. The young that hatches from the egg is called a nymph (or naiad for aquatic ones like dragonflies). It resembles a simpler, smaller version of the adult, just without functional wings or reproductive organs. It eats the same food, lives in the same place. With each molt (shedding its exoskeleton), it gets bigger and its wing buds develop, until after the final molt, it emerges as a full-fledged adult. No dramatic transformation, just steady growth.

| Feature | Complete Metamorphosis | Incomplete Metamorphosis |

|---|---|---|

| Stages | Egg → Larva → Pupa → Adult | Egg → Nymph → Adult |

| Key Differentiator | Presence of a pupal stage | No pupal stage; nymphs resemble adults |

| Larva/Nymph vs. Adult | Radically different in form and habitat | Similar in form and habitat |

| Common Examples | Butterflies, beetles, bees, flies, moths | Grasshoppers, dragonflies, cockroaches, aphids |

| Biological Advantage | Reduces competition for resources between young and adults | Simpler, faster development; nymphs are immediately adapted to environment |

I used to think the incomplete path was "simpler" or even primitive. But watch a dragonfly naiad hunt underwater with its extendable jaw—it's a perfectly adapted predator in its own right. Both paths are evolutionary masterstrokes.

A Stage-by-Stage Breakdown: More Than Meets the Eye

Let's walk through the stages, but let's skip the textbook definitions. Let's talk about what actually happens, and what you can see.

Egg: The Waiting Game

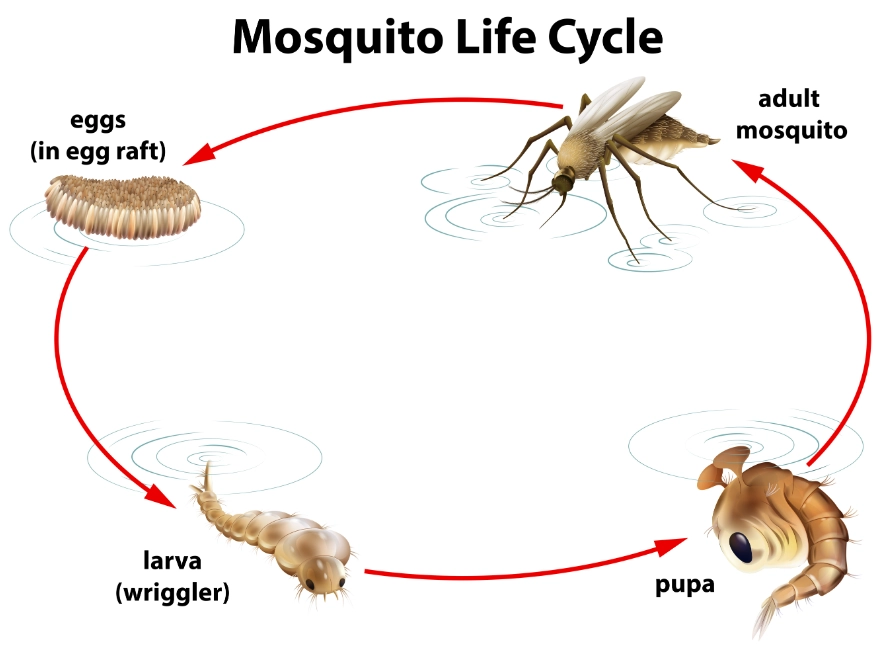

Insect eggs are architectural wonders. Butterfly eggs are often intricately ribbed. Mantis eggs come in a foamy, hardened case called an ootheca. Mosquitoes lay rafts of eggs on water. The placement is strategic. A monarch butterfly lays its egg on the underside of a milkweed leaf, the only food the caterpillar will eat. A parasitic wasp might inject an egg directly into a host caterpillar. The egg stage is all about survival and precise placement. If you want to find caterpillars, learn to find the eggs first. Look for tiny, barrel-shaped dots under leaves.

Larva/Nymph: The Growth Phase (Where the Action Is)

This is the main event. For holometabolous insects, the larva—caterpillar, grub, maggot—does nothing but eat. A monarch caterpillar increases its mass thousands of times in weeks. It will outgrow and shed its skin (molt) multiple times. Each stage between molts is called an instar. Miss a molt, and it's stuck.

For hemimetabolous insects, the nymph is a miniature adult-in-training. A dragonfly naiad lives underwater for years, hunting tadpoles and small fish. With each molt, it gets closer to its final form. The biggest mistake here? Assuming nymphs are harmless. Aphid nymphs are born ready to suck plant sap. They do damage from day one.

Pupa: The Hidden Revolution

This is the stage everyone gets wrong. The pupa (chrysalis in butterflies) is not sleeping. Inside that hard case, the caterpillar's body is dissolving into a soup of cells. Imaginal discs—clusters of cells that have been dormant since the egg stage—use this soup as fuel to build wings, compound eyes, and antennae. It's controlled chaos. Disturb a pupa at the wrong time, and you get a malformed adult that can't fly or mate. It's a fragile, critical process.

And remember: Butterflies have chrysalises. Moths spin cocoons. The cocoon is a silk casing spun *around* the pupa for extra protection. The chrysalis *is* the pupal case itself.

Adult: The Dispersal & Reproduction Machine

The adult's primary role is to disperse and reproduce. For many, like mayflies, adulthood lasts only a day or two—just long enough to mate and lay eggs. Their mouthparts are often non-functional. A luna moth doesn't even have a mouth; it lives off fat stored from its caterpillar days. This stage is fleeting. When you see an adult insect, you're seeing the very end of its journey.

Why This Matters in Your Backyard: From Pest Control to Conservation

This isn't just theory. Your garden is a stage for these life cycles, and understanding them gives you power.

Smart Pest Control: Spraying adult mosquitoes is reactive and inefficient. Their larvae (wrigglers) and pupae (tumblers) live in standing water. Eliminate the water—empty pots, clear gutters, use mosquito dunks in ponds—and you break the cycle at its weakest link. Similarly, knowing that squash vine borers are the larvae of a clearwing moth tells you when to look for eggs (at the base of stems in early summer) and cover plants with row cover before the adults emerge to lay them.

Effective Pollinator Support: Want to help bees? Don't just plant flowers for the adults. Most native bees are solitary and lay eggs in tunnels in the ground or dead wood. Leave some bare, undisturbed soil and a few dead branches. That's the nursery. For monarchs, you need milkweed for the caterpillars and nectar plants for the migrating adults. Supporting one stage without the other is like building a house with no doors.

I learned this the hard way. One year I meticulously planted a pollinator garden but kept my garden "tidy"—raked every leaf, cleared every stem. I had few butterflies. An entomologist friend pointed out I'd removed all the overwintering pupae (chrysalises camouflaged on dead stems) and egg cases. I was tidying away the next generation. Now I leave a messy corner, and the life cycles continue.

Common Missteps and How to Avoid Them

After years of watching insects, here are the subtle errors I see constantly.

Misidentifying Nymphs: People see a tiny, wingless bug and call it a "baby" something, often wrong. That tiny, red-and-black bug on your milkweed isn't a baby ladybug; it's a milkweed bug nymph. Baby ladybugs (larvae) look like spiky, alligator-like monsters. Get a good guide that shows all life stages.

Assuming All Caterpillars Become Butterflies: Many become moths! And some "caterpillars" are actually sawfly larvae (related to wasps). Count the prolegs (the fleshy legs at the back). Caterpillars have 5 pairs or fewer of prolegs, often with tiny hooks (crochets). Sawflies have 6+ pairs and no crochets.

Overlooking the Substrate: The life cycle doesn't happen in a vacuum. That soil, that leaf litter, that puddle, that specific host plant—it's all part of the story. A change in the substrate can break the cycle. This is the lever you can pull.

Your Insect Life Cycle Questions Answered

Once you start seeing the world through the lens of insect life cycles, nothing looks the same. That beetle on a flower is the end of a grub's story in the soil. That dragonfly skimming the pond just finished a multi-year underwater childhood as a voracious naiad. It's a hidden world of transformation happening all around us, full of strategy, vulnerability, and wonder. The next time you see an insect, pause. You're not just looking at a bug. You're looking at a chapter in an epic, miniature biography.

Once you start seeing the world through the lens of insect life cycles, nothing looks the same. That beetle on a flower is the end of a grub's story in the soil. That dragonfly skimming the pond just finished a multi-year underwater childhood as a voracious naiad. It's a hidden world of transformation happening all around us, full of strategy, vulnerability, and wonder. The next time you see an insect, pause. You're not just looking at a bug. You're looking at a chapter in an epic, miniature biography.