I still remember the first time I saw a Monarch butterfly emerge from its chrysalis. It was in my backyard, on a milkweed plant I'd almost pulled out as a weed. The whole thing took about an hour—the slow split, the crumpled wings, the gradual pump into vibrant orange. That moment hooked me on insect metamorphosis. It's not just a science lesson; it's nature's magic show, happening right under our noses. And you can watch it too, with a bit of know-how.

What's Inside This Guide

- What Is Insect Metamorphosis and Why Should You Care?

- Complete vs. Incomplete Metamorphosis: The Two Paths

- How to Observe Metamorphosis in Your Backyard (Step-by-Step)

- Common Mistakes Beginners Make and How to Avoid Them

- The Bigger Picture: Metamorphosis in Ecosystems and Conservation

- Your Metamorphosis Questions Answered

What Is Insect Metamorphosis and Why Should You Care?

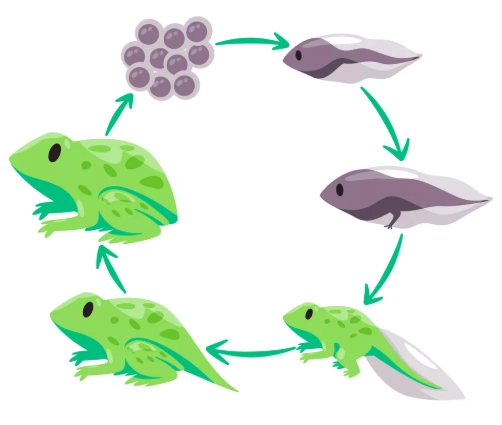

Metamorphosis is the process where an insect radically changes its form from larva to adult. Think caterpillar to butterfly, maggot to fly. But here's the thing most people miss: it's not just about looks. It's a survival strategy. Larvae are eating machines focused on growth, while adults are all about reproduction and dispersal. The Entomological Society of America notes that over 80% of insect species undergo some form of metamorphosis, making it central to insect diversity.

Why care? If you garden, understanding metamorphosis can help you manage pests naturally. Or if you're a parent, it's a hands-on science project that beats any textbook. I've used it to teach kids about patience—nature doesn't rush.

Quick Fact: The word "metamorphosis" comes from Greek, meaning "change of form." In insects, it's driven by hormones like ecdysone and juvenile hormone, which trigger molting and development.

Complete vs. Incomplete Metamorphosis: The Two Paths

Not all metamorphosis is the same. Insects follow two main routes: complete and incomplete. Get this wrong, and you might misidentify what you're seeing.

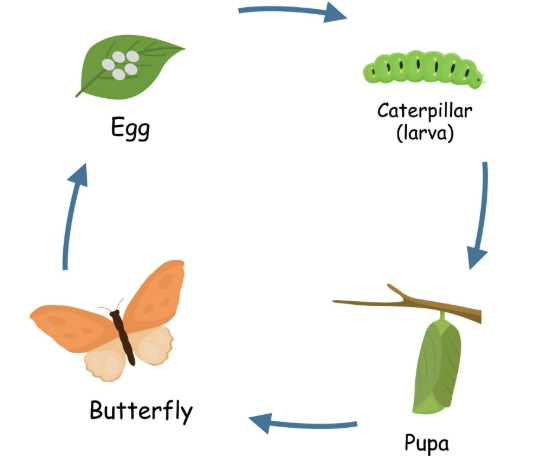

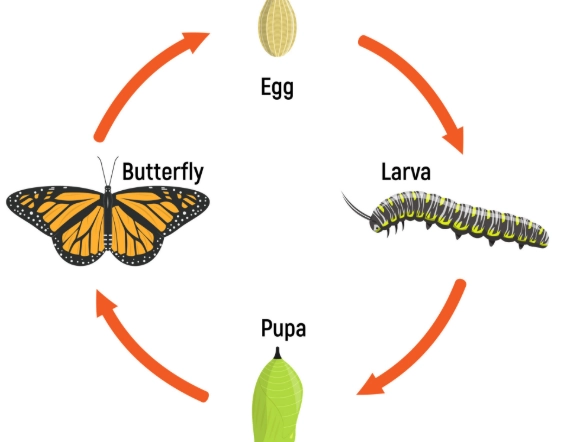

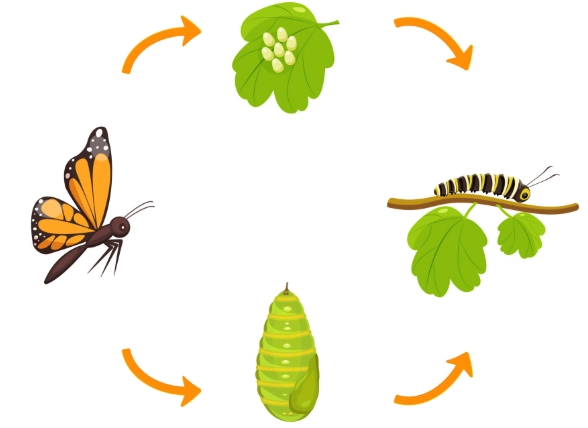

The Four Stages of Complete Metamorphosis (Holometaboly)

This is the classic caterpillar-to-butterfly story. It has four distinct stages:

- Egg: Laid on a host plant, often tiny and overlooked.

- Larva: The caterpillar or grub stage—all about eating. They molt several times, growing larger each time.

- Pupa: The transformation stage. For butterflies, it's a chrysalis; for moths, a cocoon. Inside, tissues break down and reorganize.

- Adult: The reproductive stage, like a butterfly or beetle.

Insects with complete metamorphosis include butterflies, moths, beetles, flies, and bees. It allows larvae and adults to occupy different niches, reducing competition.

Incomplete Metamorphosis (Hemimetaboly)

Here, the change is more gradual. Young nymphs look like miniature adults, just without wings. They molt through instars, gradually developing wings and reproductive organs. Think grasshoppers, dragonflies, and cockroaches. The pupal stage is absent.

I often see beginners confuse nymphs for a different species. A young grasshopper isn't a baby version of something else—it's the same insect, growing up.

| Aspect | Complete Metamorphosis | Incomplete Metamorphosis |

|---|---|---|

| Stages | Egg, Larva, Pupa, Adult | Egg, Nymph, Adult |

| Example Insects | Butterflies, Beetles | Grasshoppers, Dragonflies |

| Pupal Stage | Yes (chrysalis/cocoon) | No |

| Larva vs. Adult | Radically different | Similar appearance |

| Ecological Advantage | Reduces competition | Faster development |

How to Observe Metamorphosis in Your Backyard (Step-by-Step)

You don't need a lab. With a few simple steps, you can witness metamorphosis firsthand. I've done this with school groups, and it never gets old.

Best Insects to Start With

Choose common, easy-to-find species. My top picks:

- Monarch Butterfly: Look for milkweed plants in sunny areas. Eggs are tiny white dots on leaves. Best time: late spring to summer. Public gardens like local nature reserves often have dedicated plots—check their websites for visiting hours (usually dawn to dusk, free entry).

- Ladybug: Their larvae look like tiny alligators, often on aphid-infested plants. You can find them in vegetable gardens from April to September.

- Grasshopper: In grassy fields, nymphs appear in early summer. No special tools needed.

Avoid rare species; disturbing them can harm populations.

Essential Tools and Timing

Here's my go-to kit:

- Magnifying glass (10x): For close-ups of eggs and small nymphs. I use a handheld one from a science store.

- Clear container or mesh cage: For temporary observation. Don't keep insects locked up long—it stresses them.

- Notebook and camera: Record dates and changes. Smartphone photos work fine.

- Timing: Early morning or late afternoon, when insects are less active. Seasons matter: most metamorphosis peaks in warm months, but some moths pupate over winter.

Find a spot in your yard with host plants. If you don't have space, community gardens or parks work—just get permission. The National Wildlife Federation recommends leaving some wild areas to attract insects.

Step-by-step process: First, identify the insect and its life stage. Gently collect a specimen if needed, using a soft brush. Place it in a container with fresh leaves from its host plant. Monitor daily, but minimize handling. Release the adult after emergence.

Common Mistakes Beginners Make and How to Avoid Them

I've seen plenty of errors over the years. Here are the big ones:

- Overhandling pupae: As mentioned, touching chrysalises can be fatal. Use tools or observe from afar.

- Wrong food: Caterpillars are picky. A Monarch only eats milkweed; give it lettuce, and it'll starve. Research the host plant first.

- Ignoring humidity: Pupae need moisture. In dry setups, they desiccate. Add a damp paper towel, but not directly touching.

- Assuming all caterpillars become butterflies: Some are moth larvae, and their cocoons look different. Check guidebooks or apps like iNaturalist for ID.

My personal blunder: once, I moved a chrysalis to a "better" spot, and it fell, disrupting development. Now, I leave things be unless absolutely necessary.

The Bigger Picture: Metamorphosis in Ecosystems and Conservation

Metamorphosis isn't just a curiosity; it's ecosystem glue. Larvae like caterpillars are food for birds, while adults pollinate plants. According to a report from the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, insects undergoing complete metamorphosis contribute significantly to pollination and pest control.

But habitats are shrinking. Pesticides disrupt hormone cycles, affecting metamorphosis. What can you do? Plant native host species—milkweed for Monarchs, parsley for Black Swallowtails. Reduce pesticide use; instead, encourage natural predators. Join citizen science projects like Monarch Watch to track migrations.

It's about balance. In my garden, I let some "pests" like caterpillars be, because they turn into beneficial butterflies. The trade-off is worth it.

Your Metamorphosis Questions Answered

Metamorphosis is a window into nature's resilience. Start small—watch a ladybug in your garden. You'll see the world differently. And if you mess up, that's okay. I still do sometimes. The key is to keep observing, learning, and sharing those moments of change.