When you hear "bee," you probably picture a honey bee. But that's just one character in a much larger story. In North America alone, there are over 4,000 species of native bees, and none of them live in hives or make honey the way Apis mellifera does. They're the unsung heroes of pollination, often more efficient than their famous cousin, and they're facing a silent crisis. I've spent years watching them in my garden, from the early spring mason bees to the late-summer bumbles, and their decline isn't just an environmental footnote—it's a direct threat to the food on our tables and the health of our local ecosystems. Let's get to know them.

What’s Inside This Guide

Why Native Bees Matter More Than You Think

Here's a fact that changes the conversation: according to research cited by the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, native bees are responsible for pollinating many crops more effectively than honey bees. Tomatoes, peppers, blueberries, cranberries, and squash often rely on "buzz pollination"—a special vibration technique that bumble bees and other natives are masters of, but honey bees can't perform.

Think about your local wildflowers, trees, and berry bushes. Their reproduction is almost entirely dependent on these native pollinators. The honey bee is a managed agricultural tool, important for large-scale mono-cropping. Our native bees are the foundation of biodiversity.

And here's a subtle mistake I see all the time: people assume a pollinator-friendly garden that helps honey bees automatically helps natives. Not quite. Their needs are often distinct, especially when it comes to nesting.

How to Identify Common Native Bee Species

You don't need a PhD to start recognizing them. Just pay attention to a few key details. Size, color, behavior, and timing are your best clues.

Let's break down some of the most widespread groups you're likely to encounter. Forget complex scientific keys; this is a field guide for your back porch.

| Bee Type | Key Identifying Features | Size | Active Season | What It's Doing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

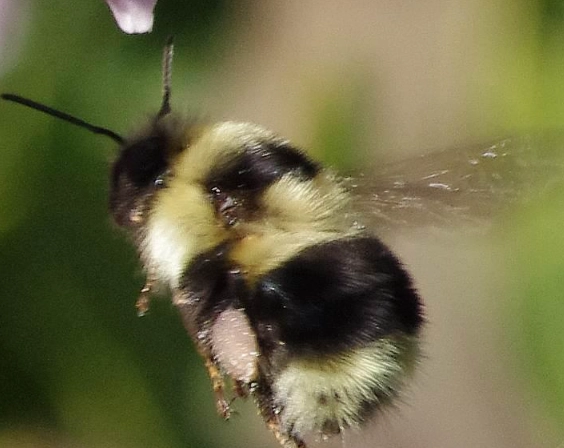

| Bumble Bee | Fuzzy, robust body with black and yellow bands (sometimes orange or white). Loud, slow flyer. | Medium to Large | Spring to Fall | Visiting deep flowers, "buzz pollinating," living in small annual colonies (50-400 bees) in old rodent nests or grass tussocks. |

| Mason Bee | Metallic blue, green, or black. Less hairy than a honey bee. Carries pollen on its belly (scopa). | Small to Medium | Early Spring | Nesting in hollow reeds or holes in wood, using mud to build cell walls. Super efficient pollinator of fruit trees. |

| Leafcutter Bee | Dark with pale hair bands on abdomen. Carries pollen on its belly. Fast, zigzag flight. | Medium | Summer | Cutting neat, circular pieces from leaves (roses, lilacs) to line its nest tunnels in wood or stems. |

| Mining Bee | Often fuzzy, resembling small honey bees. Colors vary (black, brown, reddish). | Small to Medium | Spring | Digging small, solitary burrows in bare, well-drained soil. Often forms large "aggregations" that look like bee cities in the ground. |

| Sweat Bee | Tiny, often metallic green, blue, or bronze. Some have striped abdomens. | Very Small | Spring to Fall | Visiting small flowers. May land on your skin to sip sweat for minerals (harmless). |

One of the biggest identification errors? Confusing flies for bees. Hoverflies (also called flower flies) are fantastic pollinators too, but they have huge eyes, one pair of wings, and no pollen-carrying structures. Bees have two pairs of wings and are generally hairier.

Where Native Bees Live (Hint: Not in Beehives)

This is where native bee life gets fascinating. About 90% are solitary. Each female is a single mother, working alone to build a nest, collect pollen and nectar, lay an egg, and seal it up with the next generation's food supply. No queen, no workers, no honey stores.

Nesting Habitats: The Real Estate Market for Bees

Their nesting needs are specific and often disrupted by our tidying habits:

Ground Nesters (like Mining Bees): They need patches of bare, undisturbed, well-drained soil. A perfectly manicured lawn or thick mulch layer is a housing desert for them. I leave a few sunny, bare patches in my garden border specifically for this reason.

Cavity Nesters (like Mason and Leafcutter Bees): They use hollow plant stems, beetle burrows in dead wood, or crevices in stone. When we "clean up" gardens by cutting down all dead stalks and removing every bit of fallen wood, we're demolishing their apartment complexes.

Bumble Bees: They're the social exception, but their colonies are tiny and last only one season. A queen hibernates alone, then founds a new colony in spring in an abandoned mouse nest, a clump of grass, or even under a garden shed.

The Biggest Threats Native Bees Face Today

The decline isn't due to one villain, but a perfect storm of pressures.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: This is the big one. Converting wild spaces to agriculture or development removes both food sources and nesting sites. Even in suburbs, the trend towards sterile landscapes with non-native ornamentals that don't provide pollen or nectar creates food deserts.

Pesticides: Insecticides are obvious killers, but the insidious threat is neonicotinoids, systemic pesticides that permeate the entire plant, including its pollen and nectar. The dose might not cause immediate death but can impair a bee's ability to navigate, reproduce, and resist disease. Herbicides kill the "weeds" like clover and dandelions that are critical early-season food sources.

Climate Change: It disrupts the delicate synchrony between bee emergence, flower blooming, and weather patterns. A bee might wake from hibernation to find its food flowers haven't bloomed yet, or a heatwave might wither blooms before they can be pollinated.

Disease and Competition from Honey Bees: While not the primary driver, high densities of managed honey bees can sometimes compete with natives for limited floral resources and potentially spread pathogens.

Actionable Steps: How You Can Help Native Bees Right Now

This isn't about grand gestures. It's about small, intentional shifts in how you manage your own piece of land, whether it's a farm, a backyard, or a balcony.

1. Plant a Native Bee Buffet

Focus on native flowering plants. They co-evolved with native bees and provide the best nutrition. The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center's database is an incredible resource for finding natives by region. Aim for a succession of blooms from early spring to late fall. Don't forget trees and shrubs—willows, maples, blueberries, and serviceberries are bee magnets.

Cluster the same plants together. A bee can work a patch of lavender or echinacea much more efficiently than a single, scattered plant.

2. Provide Nesting Sites

For ground nesters: Leave some bare, sunny ground. Create a small, south-facing bank of soil. Avoid tilling or walking over these areas.

For cavity nesters: Leave dead tree snags if safe. Bundle hollow stems (bamboo, reeds) and place them in a sheltered spot. If using a bee hotel, ensure tubes are cleanable or replaceable to prevent disease buildup, and mount it securely facing southeast.

For bumble bees: Leave some areas a little messy. A pile of leaves, an unmowed grassy corner, or a rodent-proof nesting box can offer a queen a starting spot.

3. Rethink Your Pest and Weed Management

This is the most powerful step. Eliminate or drastically reduce pesticide use. If you must, spot-treat problems rather than broadcast spray. Never spray on flowering plants. Embrace a few "weeds"—dandelions, clover, and goldenrod are fantastic bee plants.

4. Provide a Water Source

A shallow dish with pebbles or marbles for landing spots gives bees a safe place to drink without drowning. Change the water regularly.

I started with just a patch of native asters and a bundle of sunflower stalks left standing over winter. Within two years, the mining bees found the bare soil nearby, and leafcutter bees were taking pieces from my rose bush. It's a chain reaction of life that's incredibly rewarding to watch.

Your Native Bee Questions, Answered

How can I tell if a bee in my garden is native or a honey bee?

I see a bunch of small holes in my lawn with little piles of dirt. Is this a problem?

Should I avoid planting double-flowered cultivars to help bees?

What's the one most overlooked thing killing native bees in suburban gardens?

Are native bee hotels actually safe, or do they spread disease?