You've probably heard the term "invasive species" thrown around in news about clogged waterways or warnings at the garden center. But it often feels abstract, a problem for scientists and park rangers. Let's get concrete. An invasive species isn't just a plant or animal in the "wrong" place. It's a biological bulldozer that reshapes the world around it, costing us billions, threatening our food supply, and simplifying complex ecosystems into monotonous, fragile stands. Understanding them isn't just academic—it's the first step to protecting your own slice of the environment. This guide moves past the textbook definition and into the messy, practical reality of dealing with these uninvited guests.

What's Inside This Guide

What Makes a Species 'Invasive'?

The official definition from the National Invasive Species Information Center is a non-native organism whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic, environmental, or human health harm. But that's the sterile version. In practice, invasives share a ruthless set of traits.

They grow and reproduce incredibly fast. They're generalists, able to thrive in various conditions where native specialists struggle. They often lack natural predators or diseases in their new home to keep them in check. And they're aggressive competitors—for sunlight, water, nutrients, or space.

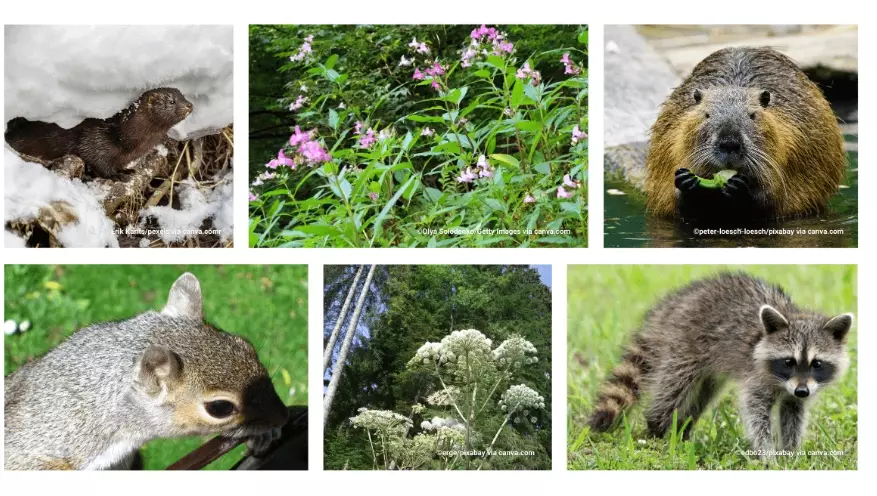

Here's a nuance most articles miss: not every non-native species is invasive. The tomatoes in your garden are non-native. The honeybee is non-native in the Americas. The problem isn't origin alone; it's the disproportionate, unchecked impact. Calling something invasive requires evidence of harm.

The Real-World Impact of Invaders

The damage isn't hypothetical. It hits wallets, health, and the landscapes we love.

Economic Costs: A Drain on Resources

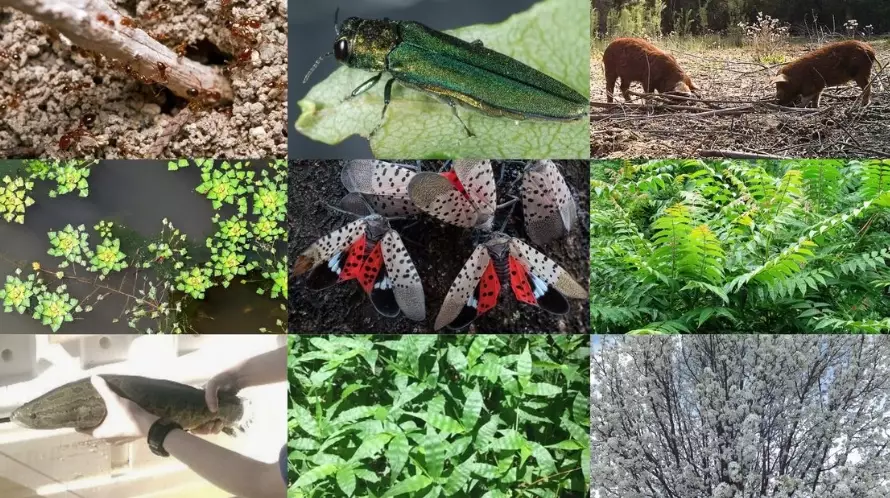

Think of the zebra mussel. This small mollusk from Eurasia infests pipes at power plants and water treatment facilities. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates control costs and damages from this one species run into the billions of dollars annually. Farmers spend countless hours and dollars fighting herbicide-resistant weeds like Palmer amaranth that can devastate crop yields.

Ecological Wreckage: Simplifying Complexity

In the Southeast, kudzu vine smothers entire forests, trees and all, blocking sunlight and killing the understory. In Florida, Burmese pythons have decimated populations of raccoons, rabbits, and even deer in the Everglades. Each loss ripples through the food web. The result is a simpler, less resilient ecosystem. When a disease or drought hits, there's no backup plan.

Human Health Directly Affected

It's not just about trees and animals. Spotted lanternflies excrete a sticky "honeydew" that fosters sooty mold, ruining outdoor areas and damaging grapevines. Giant hogweed sap causes severe skin burns and blindness. Invasive mosquitoes can introduce new diseases like West Nile virus.

The cost is cumulative and often silent until it's a crisis.

How to Identify Invasive Species in Your Area

You don't need a biology degree. You need observational skills and the right local resources.

For Plants:

- Rapid, early growth: They leaf out earlier in spring and hold leaves later in fall than most natives.

- Bare ground underneath: They often inhibit other plants through chemicals (allelopathy) or dense shade.

- Profuse seed or vegetative spread: Look for berries, runners, or root suckers spreading aggressively.

For Animals/Insects:

- Unusual abundance: Seeing huge numbers of a new insect or aquatic creature.

- Absence of damage: A new insect with no visible predators or parasites eating it.

- Physical damage signs: Unusual tree die-off, heavily skeletonized leaves, or distinctive egg masses (like the spotted lanternfly's gray, putty-like patches).

Your #1 Tool: Local Expertise. A plant invasive in Florida may be harmless in Oregon. Bookmark these resources:

- Your state's Department of Natural Resources (DNR) or Department of Agriculture website. They always have listed species and reporting tools.

- Your local University Cooperative Extension office. This is a goldmine. They have fact sheets, workshops, and experts you can email photos to.

- Apps like iNaturalist. Upload a photo, and the community (including experts) can help ID it. You can also see what other invasive species have been reported nearby.

Effective Control and Management Strategies

Once you've identified a problem, action is needed. The approach depends on the scale, the species, and your resources. The cardinal rule: Prevention is infinitely cheaper and easier than control. Clean your boat, don't move firewood, and choose native plants for your garden.

Small-Scale (Your Yard or Property)

For plants, manual removal can work if done meticulously.

- Timing is everything: Remove plants before they set seed.

- Get the roots: Many, like Japanese knotweed, can regrow from a tiny fragment. Use a digging tool, don't just pull.

- Dispose properly: This is critical. Never compost invasive plants. Bag them in heavy-duty plastic, seal them, and put them in the trash. Solarizing them in black bags in the sun for months is even better.

For insects, like the spotted lanternfly, stomp and report. Check the USDA APHIS website for the latest recommended tactics, which evolve as they learn more about the pest's life cycle.

Larger-Scale or Persistent Problems

This is where professional help or organized community action comes in.

- Chemical Control (Herbicides/Pesticides): A controversial but sometimes necessary tool. The key is targeted, responsible application. Use the right chemical at the right time (often in late fall when natives are dormant). Follow label instructions to the letter. Spot-treat, don't broadcast spray. Consider consulting a licensed professional.

- Biological Control: Introducing a natural predator from the invader's home range. This is high-science, done only by government agencies after years of testing to ensure the control agent won't become a problem itself. The successful use of a beetle to control invasive purple loosestrife is a classic example.

- Mechanical Control: Using machines or physical barriers. This includes controlled burns (for fire-adapted ecosystems), mowing at specific times, or installing barriers in water bodies.

Most successful large-scale projects use an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach, combining these methods over time.

Common Myths and Expert Insights

After a decade of working on restoration projects, you see patterns in both the invasions and the mistakes people make trying to stop them.

After a decade of working on restoration projects, you see patterns in both the invasions and the mistakes people make trying to stop them.

Myth 1: "If I remove the invasive plants, the natives will just come back." Often false. Invasives can so drastically alter soil chemistry (like changing nitrogen levels) or structure that the original native seeds in the "seed bank" can no longer germinate. You've created a vacant lot. Successful restoration usually requires active replanting with native species that can compete and hold the space.

Myth 2: "One big cleanup will solve the problem." Invasives are a chronic condition, not an acute illness. Many have long-lived seed banks in the soil. You might clear an area of mature plants, only to have a carpet of seedlings emerge the next year. The most effective strategy is the "maintenance model": an initial major effort followed by regular, shorter follow-up visits for several years to catch and remove newcomers.

The Subtle Mistake Everyone Makes: Focusing only on the green part above ground. For many perennial invasive plants, the real battle is underground. Cutting or mowing without addressing the root system is like mowing your lawn—it just comes back thicker. You must understand the plant's life cycle. Is it a taproot? A rhizome network? That dictates whether you dig, smother, or carefully apply herbicide to the cut stem.

The fight against invasive species can feel overwhelming. But it's also deeply local and personal. The patch of woods at the end of your street, your own garden, the local pond—these are the front lines. By learning to identify the threats, using proper control methods, and supporting larger conservation efforts, you're not just removing a weed. You're defending a complex, ancient network of life, one square foot at a time. Start by learning one invasive plant in your region. Then go find it. You'll never look at the landscape the same way again.